Concept Camera: The WVIL

The WVIL camera is a concept camera envisioned by Artefact’s award-winning design team. It answers the question: “what’s next for camera design?”

The patent-pending WVIL system takes the connectivity and application platform capabilities of today’s smart phones and wirelessly connects them with interchangeable full SLR-quality optics.

More information at: artefactgroup.com/wvil/

All About VR

Nikon’s VR system explained

After talking with several design engineers I’ve made a few modifications to explanations in this article. However, despite changing some of the technical description, there are no changes to my recommendations. Even after being online for some time, this article continues to generate responses and controversy. Because there are conflicting posts on other sites, people tend to disbelieve what I’ve written. All I say is: do so at your own risk. This article is based upon years of experience with Nikon’s VR system, very close analysis of testing results, talks with many other professionals, and even information from Nikon insiders. At this point, the only thing about Rule #2 that isn’t fully understood is the “why.” For that we’d need more access to the design engineers.

The first and most important rule of VR is this: never turn VR on unless it’s actually needed.

Yes, this rule flies in the face of what most everyone in the world seems to do and what Nikon implies with their advertising and marketing. The simple fact is that VR is a solution to a problem, and if you don’t have that problem using VR can become a problem of its own.

To understand that, you have to understand how VR works. In the Nikon system, VR is essentially a element group in the lens that is moved to compensate for any detected camera motion. Because this element group is usually deep in the middle of the lens, usually near the aperture opening but not exactly at the opening, you have to think about what is happening to the optical path when VR is active. Are there times when it shifts where it imparts a change to the image quality other than pure stabilization? I believe there are, though the impact is visually subtle. Some of the mid-range distance bokeh of certain VR lenses appears to be impacted by VR being on. Put another way, the background in the scene is slightly moving differently than the focus point in the optical path. This results in what I call “busy bokeh,” or bokeh that doesn’t have that simple shape and regularity we expect out of the highest quality glass.

Most people using VR don’t question the mechanics of the system. They simply believe it’s some special form of magic. It’s not. Physics are involved, not magic. And one of the physics issues is the sampling frequency. The sampling frequency of the motion detection mechanism determines what kind and how much movement can be removed. Care to guess what the sampling frequency might be? 1000Hz according to Nikon. That sounds pretty good, doesn’t it? Nope. 1000Hz is 1/1000 of a second. Nyquist tells us that we can only really resolve data accurately below half the sampling frequency, thus it can accurately only take out movements as small as 500Hz (1/500 second). While this sampling frequency is of the camera motion, it is not completely uncorrelated with shutter speed. For example, the shutter curtains only travel across the sensor at speeds above 1/250, exposing only a portion of the image at a time. Another aspect of the VR system is that it “recenters” the moving element(s) just prior to the shutter opening. Simply put, there’s a lot that has to be right at very short shutter speeds in order for there not to be a small visual impact, especially with long lenses.

But that’s not all: when you have VR turned on, your composition isn’t going to be exactly what you framed. Yes, the viewfinder shows the VR impact, but Nikon’s VR system re-centers the VR elements just prior to the shutter opening. This means that you can get slightly different framing than you saw.

Rule #2: VR should normally be off if your shutter speed is over 1/500.

Indeed, if you go down to the sidelines of a football game and check all those photographers to see how their lens is set, you can tell the ones that are really pros: VR is usually off (unless they’re on a portion of the stadium that is vibrating from fan action). Those pros have all encountered the same thing you will some day: if you have a shutter speed faster than the sampling frequency, sometimes the system is running a correction that’s not in sync with the shutter speed. The results look a bit like the lens being run with the wrong AF Fine Tune: slightly off.

The interesting thing is that pros demanded VR (IS in the case of Canon) in the long lenses, then it turns out that they very rarely use it! I’d say that less than 10% of the shooting I do with my 400mm f/2.8 has VR turned on (and by the way, I hate the rotating VR switch on some of these lenses–it’s so easy to not notice what position it is in). A word of advice: some of those previous generation non-VR exotics are relative bargains now. Consider it the VR bubble. Some day people will stop paying such silly premiums for VR over non-VR. At least they should. I know of several photographers who blew US$3000+ making the switch from non-VR to VR versions of lenses. That’s too much of a premium, I think.

Anecdotal evidence continues to pile up about VR and high shutter speeds. In hundreds of cases I’ve examined now the results are the same: the lens seems to have more acuity with VR off above 1/500. That’s my own experience, as well. A small handful of people have presented with me with evidence of the opposite (VR improves their results above 1/500). In most of those cases I’ve been able to find that it’s not VR itself that’s helping remove camera motion, but that their handholding or tripod technique is such that they’re not getting consistent autofocus without VR, but they are with it. My contention is that they’d see even more improvement by dealing with the handling and focus consistency issue and turning VR back off above 1/500.

However, as with virtually everything in photography, there’s a caveat to the above. For instance, what if you’re sitting in a helicopter shooting at 1/1000, should you use VR? One of the things that Nikon just doesn’t explain well enough is the concept of “moving camera” versus “camera on moving platform.” If the source of motion is your holding the camera steady, then what I wrote above about turning VR off above 1/500 is absolutely true. Ditto for semi-steady situations, such as shooting off a monopod. However, if there’s a platform underneath you causing vibrations (car, boat, train, plane, helicopter, etc.), things are a bit different. This is what Active VR versus Normal VR is all about, by the way. Active VR should be used when you’re on one of those moving platforms. Normal VR should be used when you’re on solid ground and it’s just you that’s shaking. Basically, if you’re vibrating due to outside source, Active VR should be On. If you’re the only source of camera movement, then use Normal.

Rule #3: If something is moving you, use Active. If it’s just you moving the camera, use Normal.

The difference between Active and Normal has to do with the types of movements that are expected and will attempt to be corrected. Platform vibrations tend to be frequent, constant, and random in direction. Handholding motion tends to be slower and move in a predictable path (e.g. when you press the shutter release hard the right side of the camera moves downward–it’s Newton’s Law, not mine). Knowing which type of motion the VR needs to deal with lets the system optimize its response.

So, getting back to our 1/1000 example while shooting on a helicopter, we have a conflict. The motion that you impart by your handholding may not get corrected right by the VR system because your shutter speed is faster than the frequency with which corrections are done. But the platform you’re sitting on is imparting small, frequent, and random motions that might actually be corrected (but probably not fully) by having VR on. The question here is whether the improvements due to removing some of the platform movement are better than the possible degradation due to the shutter closing faster than the VR is working. There’s no clear answer to that, as every situation is going to be a little different, but my tendency is to experiment with Active VR being On versus VR being totally off when shooting from platforms at high shutter speeds. I closely examine my initial results, and make my final decision based upon that. Of course, that in and of itself can be a problem for some, as examining a small screen in a moving vehicle isn’t exactly easy and precise. Still, I sometimes see an improvement with VR as opposed to without it when I’m shooting at high shutter speeds from a vehicle. At the same time, that’s not as much improvement as you’d see using a dedicated gyroscope instead of VR. If you regularly shoot out of helicopters, a gyro is a better investment than a more expensive VR lens.

Aside: There are a number of photographers that say that using VR above 1/250 (or the flash sync speed, if slower) should be avoided. Some explain that shutter speeds above that are done by moving an opening across the image rather than having the full image exposed simultaneously (this is a simplification, but it’s good enough for this discussion). Thus, VR corrections done on shutter speeds above 1/250 are correcting only a portion of the image at a time. In practice, I believe I can sometimes see very small changes at 1/500 shutter speeds versus 1/250 when VR is On. Not enough change, however, for me to alter my 1/500 limit. Above 1/500 I can much more clearly see visual changes, and changes I don’t like in my images.

At the other end of the movement spectrum, we have subject motion. If the subject is moving, using VR with longer shutter speeds is problematic. I’ve seen people use 1/15 with VR on for moving subjects. Well, even a slow-walking human has enough movement in 1/15 to cause edge blur.

Rule #4: If your subject is moving, you still need a shutter speed that will stop that movement.

This is a tough thing to learn, and it’s usually learned the hard way. Because camera makers essentially tout VR by making assertions like “allows a four-stop improvement over hand holding,” users start thinking like this: “if I can handhold my 100mm lens at 1/100, then VR would allow me to hand hold it at 1/6.” Well, maybe. But the only motion being removed is camera motion. If your subject moves during that 1/6, it’s still going to produce subject blur. Looking back at my Nikon Field Guide (page 51 for those of you following along), we get 1/125 for the minimum shutter speed necessary to freeze a person walking across the frame (1/30 if they’re walking towards you). This is, of course, a generalization. There’s a more detailed table below the one I just referenced that shows how distance impacts the shutter speed, too. Plus the size of the subject in the overall frame makes a difference. Expecting VR to remove ALL motion is something everyone has to get over:

Rule #5: VR doesn’t remove all motion, it only removes camera motion.

Another type of motion comes with panning the camera, and VR has impacts there, too. I’ve seen people say that they think you should turn VR off when you pan with a subject. There may be times when that’s true, but my experience is that VR should be on while panning. That’s because the Nikon VR system is very good about detecting a constant camera movement. If you’re doing a smooth pan in one direction, the VR system will focus on removing only motion on the opposite axis. That’s the way it’s designed to operate. The trick is to make sure that your pan is relatively smooth, and not jerky. Most people start to jerk when they press the shutter release during pans. You need to practice NOT doing that and to continue the pan while the shutter is open, not stopping. Indeed, try practicing this at your local track (or other place with some runners present). Pan with the runner and take a picture. When the mirror returned and the viewfinder view is restored after the shot is the runner still in the same spot in the frame? No? Then you didn’t continue panning through the shot. Tsk tsk. Try again. Practice until you can take a series of shots and the runner stays in the same spot through the entire sequence, both in the shots and while you’re panning between shots. You shouldn’t be having to catch up to the runner.

Aside: Back in high school my photography mentor at the time broke me of the habit of stopping during pans in a brutally sadistic way: he sent me to track meets with a TLR (twin lens reflex). You look down into the viewfinder of a TLR. But here’s the thing: left to right is reversed. So if the subject is moving right to left in front of you, they appear left to right in the viewfinder. You don’t have a chance of following motion with a TLR unless you can relax your brain and make it just mimic the motion of your subject in your own body’s motion. You can’t look and react, look and react.

Rule #6: If you’re panning correctly, VR should probably be On.

Yet another aspect of VR that confuses people is activation. Nikon’s manuals don’t make this very clear, but it really is quite simple: only the shutter release activates the VR system. A partial press of the shutter release engages it and allows it to begin a sequence of corrections. A quick full press of the shutter release engages it but it really doesn’t get much in the way of samples to rely upon and make predictions from (on the pro bodies we’re talking 1/33 of a second or so between the press and the shot being taken). Basically, if you engage VR prior to the shot, you tend to get slightly better and more consistent results. That doesn’t mean you should always wait for VR to engage before fully pressing the shutter release. If it’s time to take the picture, take the picture! VR will give it its best shot at fixing your motion when you just punch the shutter release. But there are two factors that tend to make early VR engagement a better choice if you can do it: first, the VR system gets a stream of data it can predict from; and second, it’s difficult to move the camera as much by jabbing the release if you’ve already partially pressed the release!

The usual issue that comes up with the preceding is the line in Nikon’s manual about “VR doesn’t function when the AF-ON button is pressed.” This is one of those places where the translation in Nikon’s manuals is out and out misleading. If the line had read “VR doesn’t engage when the AF-ON button is pressed” it would be more correct. In my testing VR is not “turned off” by using the AF-ON button, it simply isn’t engaged by that button press. Only the shutter release button engages VR. Thus, if you use AF-ON to focus instead of a partial shutter release, VR is not engaged during the pre-shot focusing. But it is during the shot.

This, of course, creates a slight issue. Optimally, we want VR to have a stream of data just prior to pressing the shutter release fully. If we’re using AF-ON to focus, our fingers usually aren’t pushing the shutter release partially down, too. But you should practice doing just that. Sigh. That right hand is starting to do a pretty complicated dance: AF-ON up and down for focus, shutter release partially down for VR, right thumb dialing in shutter or aperture or exposure adjustments, maybe right middle finger dialing in aperture adjustments, shutter release fully down with the index finger for the shot. This, by the way, is one of the reasons why I prefer Nikon’s ergonomics to Canon’s: at least when I’m doing all that hand juggling, my hand and finger positions aren’t really moving, especially my shutter release finger. With Canon the tendency is to move the index finger between the top control wheel and shutter release. You can react with the shutter release faster if you’re not moving that finger.

There are a few more caveats. If you’ve got a built-in flash on your camera (basically everything but the D1, D2, and D3 series), while the flash is recharging the VR system is inactive. That’s because VR takes power to perform and the assumption is that you want the flash recharged as fast as possible. Thus, the camera turns off the power to the VR system while it’s charging up the camera’s flash capacitor. If you’re shooting flash near full power and doing a lot of consecutive flashes, the flash recharge time can start taking a few seconds. How do you know if power is restored to the VR system? Well, you can’t, exactly, but the flash indicator in the viewfinder is a fairly reliable indicator: if it’s not present with the flash up and active, VR is probably Off.

Rule #7: If you rely upon VR and use flash, use an external flash instead of the internal one if you can.

I’ve been holding off on the tripod issue to the end of this article, partly because it’s not as clear cut as Nikon seems to think it is. But by now you’ve probably turned VR off, anyway ;~). Part of the problem is that Nikon hasn’t clearly labeled and distinguished their various VR system iterations. Technically, the VR II system on some of the modern lenses should detect when the camera is on a stable platform and not try to jump in and correct. But not all modern lenses have what most of us regard as the full VR II. The recently introduced 16-35mm, for example, comes long after the intro of VR II, but it does not appear to have tripod recognition. Thus, we have another rule before we get to the real rule:

Rule #8: You MUST read your lens manual and see what it says about use on tripods.

Two basic possibilities exist:

1. The manual says turn VR off when on a tripod (sometimes adding “unless the head is unsecured”)

2. The manual specifically says that the VR system detects when the camera is on a tripod

Okay, I lied. Forget what the manual says.

Rule #8 For Real: If your camera is on a tripod, even if you’re using something like a Wimberley head where it is almost always loose, turn VR off. If your tripod is on a moving platform or one that has vibrations in it, strongly consider turning VR on, but test it to be sure you need it.

So why do I disagree with Nikon? Even with a loose head on a tripod, motion should be fairly easy to control, and you should have removed one possible motion almost completely (ditto with monopods). The problem I have, and which many other pros have noticed, is that the VR tripod detection system sometimes has “false negatives.” In other words, the tripod detection mode of the VR II system should be detecting when the system is “quiet enough” to turn off corrections. Most of the time it does just that (Nikon says that the system is smart enough to detect as many as three different types of motion–handholding, platform vibration, and support system movement–because the “vibrations” caused by each of these are recognizable different in wave form). Every now and then, though, VR thinks it needs to correct when it doesn’t (or perhaps is still correcting for a previously detected motion that will no longer be present in the next sampling). When that happens, the VR element(s) are moving when they shouldn’t be. Usually not a lot, but enough to make for less than optimal results.

Indeed, this is the very same problem as with using VR over 1/500: sometimes it works, sometimes is doesn’t. The problem is that you won’t like it when it doesn’t, and you won’t know when it does. If I were to tell you that out of 100 shots you take 10 were going to be bad due to the VR doing the wrong thing, would you still use VR? Remember, when you’re on a tripod, all 100 shots should be good without VR (otherwise you have the wrong tripod and head, see this article, or you’re using poor technique). I’m not a gambler: I prefer the known to the unknown, so I don’t like having random shots spoiled by VR.

Which brings up a whole different topic: what does a spoiled-by-VR shot look like? Well, “spoiled” is perhaps too harsh a term. Sub-optimal is probably a better one. An optimal shot has very clean and well defined edge acuity. Assuming a “perfect lens,” edges should be recorded basically as good as the anti-aliasing filter, sensor, and Bayer demosaic allow. What a lot of us find when VR is not quite correcting as well as it can/should is that edges get a little bit of “growth” to them, and sometimes there’s a directionality to that growth. It’s sort of like camera movement, only much more subtle. I tend to say that the detail “looks busy” when VR isn’t fully doing its job or is on when it shouldn’t be. And when you apply sharpening to busy edges, that busy-ness gets busy-er. Without VR active at all while on a stable tripod, it’s like a veil gets lifted and you suddenly see how sharp your lens really is (assuming you correctly obtained focus on your subject and had a stable platform, that is ;~).

Yes, there’s some nitpicking going on here. VR not correcting right is a bit like tripod mount slop (fixed with a Really Right Stuff Long Lens Support) or ringing vibrations in the tripod legs (fixed by using the right legs for your equipment): you don’t see it until it’s gone, and even then usually only if you’re pixel peeping. But someone using a 400mm f/2.8G VR lens on a D3x spent a lot of money on equipment to get the best results. They expect to be able to catch every bit of detail and blow it up into a large print. As always on this site, you need to understand that I always write about the search for optimal bits. If you’re shooting with a 16-85mm on a D300 and putting 640×480 images on the Web from that, well, whether the VR missed doing its job by a little bit probably isn’t so important.

If there are more questions on VR I’ll address them in the Discussion at the bottom of this page. Until then, here’s your motto: VR stays off unless I specifically need it. VSOUISNI and prosper.

Discussion:

- “Which lenses are VR I and which VR II, and what’s the difference?” The difference is vague, as Nikon hasn’t really released enough information to say much more than VR I claimed to give a three-stop advantage while VR II claims a four-stop advantage. Yes, in practice, the new VR seems to do a slightly better job, but it’s unclear as to why it does a better job. Lenses that are still VR I include: 18-55mm, 18-105mm, 24-120mm, 55-200mm, 80-400mm, and the 200mm f/2. Lenses that are VR II include 16-35mm f/4, 16-85mm DX, 18-200mm II, 70-200mm II, 200-400mm II, and 300mm II.

- “Does VR make a lens more likely to fail and need repair?” Possibly. I’ve had one VR failure that needed repair and I know of others who’ve had similar failures. Still, it’s rare that a lens has a mechanical failure, though adding the complexity of the VR mechanics certainly must increase the likelihood of encountering a problem.

- “My VR is on occasion very jumpy.” Check your camera’s battery level when that happens. I’ll bet that it is low. When you run batteries way down and activate VR it appears that the VR system can sometimes demand more power than the camera can supply instantaneously. The result is “jumpy VR” as the VR circuitry cuts in and out. I consider it just another “low battery” warning ;~). But see the “jumps after a shot” comment, below.

- “Don’t you get some effect from VR even if your shutter speed is above 1/500? After all, the VR elements are probably moving between samples.” Yes, sometimes you get a VR-like effect above 1/500, and it’s probably because the elements are in near constant motion and the designers have picked a movement frequency and smoothing curve that takes advantage of the known sampling frequency. But the problem with using VR above 1/500 is that you will get clear image degradation often enough that you’ll get burned by it. And I believe you get burned by it more often than you’d get burned by having VR off. Again, Nyquist tells us that when we sample something, we can only be “precise” about our data at one-half the frequency. Above that you don’t get useful data, and a mechanical system can induce ringing effects as it tries to adjust. Let’s see if I can explain it simply (a very gross generalization and simplification coming up): Pretend we’re moving enough to impart a different motion that needs new correction ten times a second. Assume we’re sampling five times a second. So what if we move Left, Right, Down, Left, Up, Right, Right, Left, Down, Up? The sampling sees Left/Right, Down/Left, Up/Right, Right/Left!, Down/Up! See the problems? If we take images at ten frames a second, the system is lagging us in the first few samples and may settle down while we’re still moving in the last two. The problem with Nyquist is that there’s a strong chance that the system is going the opposite direction you want it to when you exceed the sampling frequency. But, yes, there’s a chance that it’s going the right direction, too. Not a good enough chance to use VR, in my opinion. Moreover, I don’t know of a working sports or wildlife pro using the long lenses that hasn’t discovered the same thing by practice: VR tends to degrade shots above 1/500.

- “Does VR stabilize the autofocus system?” Yes. And this can be important in a few instances. It’s one of the reasons why I argued that not putting VR into the 24-70mm lens was one of Nikon’s bigger mistakes in the last decade. If you’re moving the camera enough that the autofocus sensor(s) you’re using isn’t staying stable on the point you want focused, there’s a chance focus will shift to someplace you don’t want it. Your Lock-On and other autofocus settings interact here, so it’s not a 100% certainty that VR will improve your autofocus results, but it does just enough that I find it useful to have the option. At wide angles, the AF sensors can easily get distracted by backgrounds. Nikon vaguely warns about this in their manuals (fifth example, D700 manual page 80). So if you’re moving the camera enough that the background is getting onto that autofocus sensor with regularity, that can be a problem, and VR might help.

- “The viewfinder jumps after a shot.” This is normal. Note that the Nikon VR system operates differently for pre-release focusing: the viewfinder image is stabilized, which means the VR elements may have moved off center to provide a stable view (also impacts focusing, see question just above). But during the exposure the system does a few different things. First, it recenters the VR elements. Second, it uses a different algorithm for doing its correcting. It very well may be the recentering action that causes some of the above 1/500 issues, by the way.

- “What about monopods or beanbags?” Nikon tends to recommend having VR on with monopods in most of their manuals. Personally, I think this really gets down to a handling issue, though. One of the primary camera motions that VR is often correcting is the “shutter release stab,” which tends to impart a forward or backwards tilt in the camera. Proper use of a monopod tends to (mostly) remove that component, leaving side-to-side as the primary camera movement needing correction. So it starts to depend upon what’s causing that side-to-side motion. Following action that moves in one direction? That’s panning (see above). Following action that moves back and forth? Be careful of the shutter speed. At low shutter speeds (which would need VR) subject motion is going to be your biggest issue. At high shutter speeds, you’re turning VR off anyway. This gets back to my “VR should be off unless needed” rule: there’s actually a very narrow window of shutter speeds that make sense to have VR on with moving subjects, perhaps as narrow as 1/125 to 1/500. Subject isn’t moving but you can’t hold the camera still on the monopod? This would be a case where VR probably should be on.

- “Do sensor-based stabilization systems have the same rules?” This article is specifically about Nikon VR. It also seems to apply fairly well for Canon IS, which is a very similar system. I can’t say that the sensor-based systems do or don’t act the same. I have a suspicion that they do, which means that burying the on/off for it in menus is the wrong approach for optimal results. That’s because it encourages people to just leave it on all the time. Nevertheless, I don’t know enough and haven’t tested enough to know for sure.

Something that’s coming up with many of the email questions is more basic than the specific questions. It appears most people just want to be told “use it for X, don’t use it for Y.” While I can broadly suggest probable use patterns, VR is just another one of those decisions that photographers have to make when evaluating each situation they encounter. Taking shortcuts with decisions ultimately leads to less-than-optimal results. For casual shooting, shortcuts perhaps work just fine for most people, and I’ve suggested a bunch in this article. But for serious shooting where quality matters, a good photographer is always evaluating, always testing. In some ways, digital is great for that, as we have an immediate feedback loop and can test a setting assumption almost immediately, plus we have the ultimate loupe in our large computer monitors.

Thus, one other point I’ll make is that I can’t tell you every possible time you need to use VR and every possible time you shouldn’t. What I do know is that when VR has been on when it shouldn’t be, my images suffer. And yes, when I shoot without VR on when it should be, my images suffer, too. However, generally I know when I’m imparting substantive motion to the camera during shooting. Thus, VR is off unless I know that I’m imparting motion, and then I only turn it on if I can guess–and verify with a field test–that it will remove that motion.

One thing I’ve noticed is that those of us who shot with long lenses back in the film days prior to VR aren’t quite so fast to turn it on as someone picking up a camera today. Part of that is the marketing message (“up to four stops better!”), but the real reason why the old-timers tend to use VR only on occasion and mostly correctly is that we already had to figure out when we were imparting camera movement prior to VR being available. We either had to correct the underlying problem or not shoot. Thus, we tend to know when we’re on the margin where VR might be helpful. I’d argue that leaving VR on and turning it off only when you see a degradation (which may be too late if you’re seeing it when you get home and looking at images on your monitor) isn’t easily learned. Leaving VR off and turning it on only when you see a degradation is much more easily learned.

Source:

Thom Hogan

Other links:

Nikon – about VR (Vibrating Reduction)

Nikon – Tech Specs

Photo:

Nikon

50 Greatest Cameras of All Time

A photographer’s ‘first’ camera will always be the one which holds a special place in their heart, whatever we move on to owning. Some of us remain loyal to one brand, one manufacturer or one model throughout our photographic lives. Others are happy to jump to the latest ‘next’ thing or the ‘hot’ model of the time. Whichever route you take when it comes to owning cameras, there is always a certain sense of nostalgia for those cameras from the past and there are few better ways to spend your non-shooting time than by compiling the ‘greatest ever’ list.Rather than just rely on our personal likes and dislikes, we asked the country’s retailers to supply us with their top ten lists and a few of our Photography Monthly Masters to chip in with their votes to help us compile the 50 greatest cameras of all time in no particular order. They are all winners in our eyes. Is it the ultimate list? Or just a good starting point? Only you can decide; either way, for some of you it will be a trip down memory lane and for others an introductionto some of the forgotten classics.

50 Yashicamat 124The Yashicamat 124 is a twin-lens reflex (TLR) that is based on the much more expensive and iconic Rolleiflex system of medium-format cameras and was first introduced in 1957. It’s a capable camera with a good lens and the perfect low-price introduction to shooting square-format images.

49 Nikon D300sAnother big favourite with our readers. The D300S is a 12.3 megapixel DX format model launched in 2009. It replaced the D300 as Nikon’s DX format flagship DSLR by adding HD video recording (with autofocus). It has similarities to the Nikon D700, with the same resolution, but has a smaller, higher-density sensor.

48 Pentax K1000The K1000 was produced from 1976 to 1997 and if you went to art school during this period it was probably the camera you were given to use. They are still being handed out today! The K1000’s longevity makes it significant, despite its ordinary design. It was already technically obsolete in 1976, but its inexpensive simplicity made it a popular workhorse.

47 Sinar Norma Invented in 1947 asa large-format camera ofhigh precision and simple operation, with a system of parts that were readily interchangeable. The name Sinar is an acronym forStudio, Industry, Nature, Architecture, Reproduction, which sums up the versatility of the system. The Sinar Norma, made from 1947 to 1970, is a technological and industrial design icon.

46 Nikon D90The D90 is a 12.3 megapixel model launched in 2008 to replace the D80 and it is a firm favourite with our readers. The updated model includes live view capability and automatic correction of lateral chromatic aberration. It was also the first DSLR to offer video recording, with the ability to record HD 720p videos, with mono sound, at 24 frames per second and has a high resolution rear LCD screen. A built-in autofocus motor means that all Nikon F-mount autofocus lenses (except for the two rare Nikon F3AF) can be used in autofocus mode. The D90 was also the first Nikon camerato include a third firmware module, labelled ‘L’, which provides an updateable lens distance integration database that improves autoexposure.

45 Canon F-1The Canon F-1 was producedby Canon from 1971 to 1976 and was the model that saw the introduction of the Canon FD lens mount. The F-1 was Canon’s first truly professional-grade SLR system, supporting a huge variety of accessories and interchangeable parts so it could be adapted for different uses and preferences.

44 Pentax Auto 110Launched in 1978 the Pentax Auto 110 and Pentax Auto 110 Super were single-lens reflex cameras made by Asahi Pentax. The Auto 110 was introduced with three interchangeable lenses. A precursor to today’s compact camera systems it claims to have been the smallest interchangeable-lens SLR system created made to professional quality.

43 Pentax K20DThe K20D body was developed by Pentax while its CMOS sensor was manufactured by Samsung, which became Pentax’s partner in 2005. Until 2008, the K20D held the record for the highest resolution sensor in theAPS-C image sensor format,at 14.6 megapixels.

42 Hasselblad 503CWThe Hasselblad that brings old school to new ways. The 503CW can deal with analogue and digital capture thanks to the range of digital backs available. The perfect option for those unwilling to give up film.

41 Sony Alpha 900The α900 is Sony’s current flagship digital SLR, introduced in September 2008. As well as a hostof pro features it includesa massive 24.6 megapixelfull-frame CMOS sensor which makes it an obviousinclusion in our list forthat reason alone.

40 Canon T90 A lot of you still seem to be very fond of the Canon T90, which was first introduced in 1986, as the top of the line in Canon’s T series of 35mm SLRs. It was the last professional-level manual-focus camera from Canon, and the last professional camera to use the Canon FD lens mount. Although it was rapidly overtaken by the autofocus revolution and Canon’s EOS (Electro-Optical System) cameras after only a year in production, the T90 pioneered many concepts seen in high-end Canon cameras up to the present day, particularly the user interface, industrial design and high level of automation. Due to its rugged build, the T90 was nicknamed ‘the tank’ by Japanese photojournalists. Many photographers and retailers still rate the T90 highly even after 20 years as it is considered by many to have been the best slr Canon ever.

39 Nikon D2X The D2X is a 12.4 megapixel camera which was launchedby Nikon in 2004. The D2X was the highest resolution flagship in Nikon’s DSLR line until June 2006 when it was supplanted by the D2Xs and later by the Nikon D700 and Nikon D3, both using a newFX full-format sensor.

38 Olympus OM-1 The OM-1 really is one of the most loved and highly regarded of film SLRs. The first model was launched in 1972 and was called the M-1. Thirteen years earlier, the release of the Nikon F had made the 35mm SLR the standard choice for professionals accustomed to using Leicas and other rangefinders, but it had driven the market towards heavy and bulky cameras. The Olympus M-1 changed all that and with it began a reduction of size, weight and noise of the 35mm SLRs. Since Leica’s flagship rangefinder cameras are known as the M Series, the company complained about the name of the M-1, forcing Olympus to rename it theOM-1. The OM-1 is an all-mechanical SLR with a very large viewfinder with interchangeable screens but a fixed prism. It also featuresa through-the-lens exposure meter and, quirkily, has the shutter speed dial around the lens mount rather than on the camera’s top plate. It’s not fashionable but it is brilliant.

37 Nikon D40Despite having been on the market since late 2006, the D40 still has some benefits over its newer rivals. Because only six megapixels are fitted on to the standard Nikon DX format sensor, the sensitivity of each pixel is higher. The default sensitivity is ISO 200 and it adds an ISO 3200 speed (listed as ‘Hi1’ in the camera menu). The D40 has a very fast 1/500 flash sync, useful for daytime fill-flash. This compares to the typical 1/200 sync speed of other entry level and even some semi-pro DSLR cameras. But the D40 lacks a built-in autofocus motor, so only Nikon lenses with AF-I, AF-S or compatible focus motors can be used in autofocus mode.

36 Canon EOS 5DThe EOS 5D, launched in 2005, was a landmark camera. It was a 12.8 megapixel DSLR and the first with a full-frame sensor at an incredibly low price which made professional quality digital images available to all. The professional market changed overnight and despite what are now considered low ISOs, the 5D remains amuch-loved industry favourite.

35 Mamiya RZ67The RZ67 is the mediumformat workhorse of the pro industry and a modularsystem, meaning that lenses, viewfinders, ground glasses, film winders and film backsare all interchangeable. The RZ67 is designed primarily for studio use, but is often usedon location as well.

34 Panasonic DMC-LX3The Panasonic Lumix DMC-LX3, or LX3, is a high-end compact camera launched in 2008 as a successor to the LX2 and continues to be oneof the best high-end compact point and shoots available.

33 Nikon D700 Another much-loved recent model from Nikon, the D700 is a professional grade dslr launched in 2008. It uses the same 12.1 megapixel FX-CMOS image sensor as the D3 and is Nikon’s second full-frame digital SLR camera. The D700’s full-frame sensor allows the use of non-DX F-mount lenses to their fullest advantage, with no cropfactor. The D700 bearsa physical similarity to the D300 and has a built-in autofocus motor for all Nikon autofocus-lenses, includes CPU and metering for older Nikon F-mountAI/AI-S lenses, and supports PC-E lenses.

32 Canon A-1Launched in 1978 the A-1 is historically significant because it was the first SLR to offer an electronically controlled programmed auto-exposure mode. Instead of the photographer picking a shutter speed to freeze or blur motion and choosing a lens aperturef-stop to control depth of field (focus), the A-1 has a microprocessor programmed to automatically select a compromise exposure which is based on light meter input. Virtually all cameras today have at least one program mode.

31 Nikon FM2 The FM2 was designed notfor budget minded snappers who would never take the time to learn to use shutter-speeds and aperture settings, but instead to appeal to serious photographers who demanded a tough, rugged camera.At the time of the FM2’s launch in 1982, Nikon believed that advanced photographers were not interested in every latest technology, but instead favoured high quality and precision workmanship.The FM2 is very mucha photographer’s camera.

30 Pentax ME FThe ME F was the first autofocus (AF) 35mm SLR camera to reach production. It had a built-in through-the-lens (TTL) electronic contrast detection system to automatically determine proper subject focus and drive a lens to that focus point. Although it auto-focused poorly and was a commercial failure, the ME F wasa milestone in camera technology, pointing the way to present-day AF SLRs.

29 Rolleiflex TLRThe Rolleiflex medium-format TLR (twin lens reflex) film cameras launched in 1929 were loved for their compact size, light weight, superior optics, durable and simple mechanics and bright viewfinders. The mechanical wind mechanism was robust and clever, making film loading semi-automatic and quick. A wide range of accessories made this camera a more complete system, allowing close-ups, added filters and quick tripod attachment. Still much loved and used, particularly by art photographers.

28 Nikon SP RangefinderThe SP is a professional level, interchangeable lens, 35mm film, rangefinder camera launched in 1957 as the culmination of Nikon’s RF development which began in 1948 with the Nikon I. It is considered the most advanced rangefinder of its time.

27 Bronica EC-TLIIOften unfairly seen as the poor man’s Hasselblad, the ‘Bronnie’ was many people’s first medium-format camera. A reasonable price combined with a huge range of lenses available made the ‘Bronnie’a great enthusiast’s choice.

26 Hasselblad 500ELIn 1964 Hasselblad started production of the motorised 500EL. Apart from the housing that incorporates the motor drive and the batteries, the EL was similar in appearance and operationto the Hasselblad 500C and uses the same magazines, lenses and viewfinders.

25 Leica M9The latest in the legendary rangefinder M series from Leica and only the second ina digital format featuring an 18.5 megapixel sensor.

24 Holga 120NFew cameras create their own aesthetic but the Holga definitely has. It is an inexpensive, medium-format 120 film toy camera, made in China. The Holga’s low-cost construction and simple lens gives pictures that display vignetting, blur, light leaks and other distortions, all of which have led to the camera gaining a cult following.

23 Kodak Retina IIICThe Retina, launched in 1936, was a compact folding camera which pioneered the 135 film format. The IIIC first appeared in 1957 and was the fifthand final development ofthe original model.

22 Olympus Pen E-P1Beautifully designed and named after Olympic’s original half-frame 35mm Pencameras launched in 1959, the E-P1 is another of the cameras leading the way in the compact system revolution.

21Canon EOS 7DJust as you were saving up for a 5D MkII, Canon brought out the 7D and made many of the qualities of the MkII available at an even lower price, even adding a host of facilities new to the EOS range.

20 Olympus TripThe Trip 35 was introduced in 1967 and discontinued in 1984. The name referred to its intended market, people who wanted a compact camera for holidays. More than ten million were sold. This point and shoot model had a solar powered selenium light meter and just two shutter speeds. Although the Trip is coming back into fashion due to its quality and ecological credentials, you can pay as little as £10 for one.

19 GandolfiThe maker of one of the greatest handmade large-format cameras ever made. Based in London, ithas been making and repairing cameras since 1885.

18 Pentax 6x7A fond favourite of any pro who worked with it throughout the seventies and eighties despite its weight and tendency to spend more time being repaired than used. The Pentax 6×7 looks like and is operated like a regular 35mm SLR camera but is loaded with either 120 or 220 roll film, which produces 10 or 206×7 format exposures. You have to love this camera with its wooden handle attachment and tank-like construction.

17 Rollei 35 The Rollei 35 is a 35mm miniature viewfinder camera launched in 1966, when it was the smallest 135 film camera ever. Even today the Rollei 35 series remains the smallest mechanically working 35mm cameras ever built.

16 Zeiss Contaflex Super BC The Contaflex SLR, introduced in 1953, was one of the first 35mm SLR cameras equipped with a between-the-lens leaf shutter. The Super, launched in 1959, is easily recognisable by the wheel on the front plate for setting the aperture.

15 Leica IIIThis quirky rangefinder launched in 1933 used a coupled rangefinder distinct from the viewfinder. The latter was set for a 50mm lens and to use other lenses required an alternate viewfinder on the accessory socket.

14 Olympus PenThe Pen half-frame, fixed-lens viewfinder cameras were made from 1959 to the start of the eighties. The original was one of the smallest cameras to use 35mm film in 135 cassettes.

13 Polaroid SX-70The original SX-70 was beautiful with a folding body finished in brushed chrome and tan leather panels. It had a whole array of accessories, including a close-up lens, electrical remote shutter release and a tripod mount.

12 Ilford WitnessThe Ilford Witness was a rangefinder with interchangeable lenses announced in 1947, but not released until 1953 because of manufacturing difficulties. A true industry secret due to its quality and rarity.

11 Panasonic GF1Released in 2009, the GF1 has a strong following among pro and enthusiast photographers as a compact system camera which can change the way you can create images. Great quality of build and image.

10 Canon eos 1D MkIV The 1D has always been the peak of Canon’s camera range in all its different forms. However, the MkIII didn’t make many friends and took a little of the shine off the 1D for some. The MkIV has converted those doubters. It’s a solid piece of pro kit that gets everything right including making the 1D first choice again.

9 Nikon FIntroduced in 1959 and an instant classic, the Nikon F introduced the concept of the modular 35mm single-lens reflex camera (SLR) and changed the way in which photographers could take pictures, from the fashion studios of swinging London to the war zones of Vietnam.The F-bayonet mount isstill in use today, andremains essentially unchanged, except for some minor refinements to keep pace with technology.

8 Leica M4A classic within the legendary M series, the M4 was introduced in 1967 and is the direct successor of the M3and M2. Three ergonomic modifications were introduced in the M4: A different, angled film advance lever, as well as slightly different rewind,self-timer and frame selection levers; a crank for rewinding the film, replacing the telescopic knob of the M3;and a faster loadingsystem that did not needa removable spool.

7 Mamiya 7IIThe Mamiya 7II is a medium format 6x7cm rangefinder camera with interchangeable leaf shutter lenses but is no bigger than top 35mm SLRs. Quiet, compact and lightweight, the 7II has a panoramic adaptor accessory that can also be added for true 24x65mm panoramic images.

6 Canon EOS 5D MkII The camera which brought about the birth of convergence between photographers and filmmakers. The 5D MkII has become a landmark camera which is being used by pro photographers and Hollywood film-makers. The final episode of the US medical drama House was shot on a 5D MkII.

5 Contax RTS-3The RTS (short for Real Time System), was created by the Porsche Design studios and was the beginning of the new Contax line of SLR cameras which brought 13 different models. The RTS-3 became an instant hit with pro photographers the moment it was launched due to its looks, build and image quality.

4 MinoxMinox is famed for its subminiature cameras. Originally launched as luxury items, they gained notoriety as a spy camera during the Second World War. Production moved from Latvia to Germany after the war. Minox continues to make miniature cameras today. Just keep it secret!

3 Hasselblad 500CM The professional’s first choice medium-format camera for more than 40 years. The 500 was the second generation of the Hasselblad 6x6cm format film and was launched in 1957. Strong build, high-quality lenses and ease of use have made it the professional photographer’s friend, whatever they are shooting.

2 Nikon D3sThe latest top pro offering in the Nikon range. The D3s has broken new ground with its incredibly high ISO capability and super tough build and construction. Designed to meet the needs of the most demanding of pro photographers, it deliversand then some.

1 Kodak BrownieThe Brownie, launched in 1900, popularised low-cost photography and introduced the concept of the snapshot. The original cardboard box camera took 2.25in sq pictures. The 127 modelsold millions from1952 to 1967.

A special thanks to: www.croydonphotocentre.co.uk , www.classiccameraexchange.com , www.waltersphotovideo.com , www.arundel-photographica.co.uk , www.parkcameras.com , www.mathersoflancashire.co.uk , www.graysofwestminister.co.uk , www.1stcameras.com

Ansel Adams’ Home and Darkroom

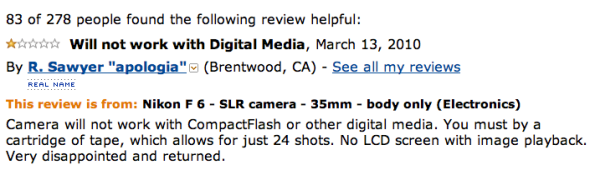

Review of a Nikon F6 on Amazon

You Must By a Cartridge of Tape

…Richard Fee found this review of a Nikon F6 on Amazon, via R.O. Teague’s twitter:

Now, this could well be a joke, and probably is. But none of the guy’s other reviews are ironic, sarcastic, or humorous, and just the possibility that this could be sincere was enough to make me chuckle.

I especially like the line “You must by a cartridge of tape.”

Mike

(Thanks to Richard)

Featured Comment by Slobodan Blagojevic: “…And 83 people found his review actually helpful…now, that is really scary. 😉 ”

UPDATE from Quan Ha: “The reviewer did eventually chime in to let everyone in on the joke:

Posted on Feb. 20, 2011 9:51 PM PST / Last edited by the author 1 hour ago / R. Sawyer says: Thanks for the compliments! Glad my review is HELPFUL to so many people (Holy moly—210 and counting!). I wrote this review after spending weeks on a mundane writing assignment while I was in my last year of law school. Tired of the lengthy techno-group-think reviews found everywhere on camera sites, I wanted to write something pithy, and satire is my favorite form of humor. […] Hopefully this inspires more of you to sprinkle fun reviews throughout the web. However, be cautioned: as many of these angry comments suggest, satire is the fine wine of humor, and you may want to start with something more universally understandable like puns. The best part about this “15-minutes of fame” is that my wife now thinks that I might actually be funny. Sense of humor validated. Now for a shameless plug, Ken Rockwell style—www.HollisterRanch.com <—shameless plug for my business.

“83 out of 278 people found the review helpful!” What more can I say?! :))

Source: the online photographer

Pete Eckert

Pete Eckert is a totally blind person. But through his photography, he proves that he IS a visual person, he just can’t see.

Pete was the Grand Prize recipient of Artists Wanted: Exposure 2008, an international photography competition, and was awarded $2,008 with a formal reception at Leo Kesting Gallery in New York City on Thursday August 7, 2008.

Thank you, Pete! A great story!

For more information: ArtistsWanted.org

Vivian Maier: A life’s lost work seen for first time

The photographs reveal teeming streets, children at play in an alley, couples captured in a sleepy embrace, the intricate latticework of an elevated train platform, a drunk smeared in filth.

The arresting, artfully framed scenes from the streets and byways of New York, Chicago and beyond seem alive with movement. And for years, they were probably seen by no-one but the solitary Chicago nanny and amateur photographer who shot them.

But now, two years after her death in a nursing home, Vivian Maier is finally being recognised for her talent after a lifetime of obscurity.

Her life’s work, hundreds of thousands of black and white and colour photographs, was locked away in an abandoned storage unit, only to be revealed to the world after her death.

Maier was born in New York City in 1926, but many details of her life remain a mystery.

She spent some of her formative years in France and when she moved to Chicago after World War II to work as a nanny, she spoke with a French accent that delighted her charges.

Years later, the children she looked after described her as a Mary Poppins-like figure who took them on wild adventures and showed them unusual things.

According to those who knew her, Maier was opinionated and incredibly private. She worked for one family in Chicago for 17 years and as they tell it, she neither made nor received a single telephone call the entire time.

Remarkable trove

On her days off, she would walk the streets taking photographs, poignant and humorous scenes from everyday life. A man sleeping on the beach, children smiling, a woman dressed in her finest climbing into a ’57 Chevy.

Her black and white photographs, many taken in the 1950s and 60s, captured the energy and feeling of the world as she viewed it.

But as far as anyone knows, she never showed her work.

In 2007, John Maloof, then a 26-year-old real estate agent in Chicago, was working on a book about his north-west Chicago neighbourhood.

At an auction of the contents of an abandoned storage unit, he paid $400 (£252) for a box of what he thought were negatives of historical architecture photographs.

But after inspecting them, he saw that none of the roughly 30,000 negatives were architectural photographs and, disappointed, he set the box aside.

About two years later, curiosity got the better of him and he began developing the negatives and scanning them one by one into his computer. And he began to realise he had stumbled across a remarkable trove.

“It wasn’t a ‘eureka’ moment,” he says. “Over time, she taught me that her work was good. I looked at her photos and learned about photography, how hard it is to take a good photograph.”

A novice to photography, Mr Maloof knew little about what he was viewing. Seeking feedback, he posted some of her work on the popular photography site Flickr. The response was overwhelming: hundreds of comments from shocked and impressed viewers.

Maier’s quick eye and artful technical skill have garnered something of a cult following online.

She has been compared to great photographers Robert Frank and Walker Evans, and as more people discover her work, her stature continues to grow.

Seeking clues

Once Mr Maloof realised how special the work was, he set out to learn the photographer’s identity. On the back of an envelope in one of the boxes, he found written the name Vivian Maier.

A Google search revealed a just-published obituary: Maier had died at 83 just three days earlier.

Using clues gleaned from the obituary, he got in touch with some of the families that had employed her over the years, and a picture of her life began to come into focus.

“She was a loner, a solitary person, she died alone with no kids or family or love life,” Mr Maloof says.

He sees her as a patron for the poor, using her camera to give a voice to the voiceless. Many of her subjects live at society’s margins, and her images show the truth about what she saw around her, not just the beautiful, Mr Maloof says.

He says she inspired him to become a photographer, and he set himself to saving the rest of her work.

He estimates he now has acquired 95% of her work from other collectors: hundreds of thousands of negatives, undeveloped rolls of film. He has been diligently developing and scanning her work and posting the photos on a blog he created for the collection.

Although Maier was a private person and kept her work to herself, Mr Maloof has received inquiries from exhibitors, book publishers and filmmakers, and her photographs have been shown in Denmark and Chicago.

“She was using photography to fill in a void emotionally, perhaps to satisfy herself,” Mr Maloof said. “The work has a life of its own. People want to see it.”

Source:

BBC (By Katie Beck BBC World News America)

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-12247395

Youtube

Other links, other stories and Maier’s photos:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-12247541

http://vivianmaierphotography.com/

http://vivianmaier.blogspot.com/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vivian_Maier

Stare

Happy New Year!

La multi ani tuturor! Va doresc un an mai vesel si plin de zambet si lumina buna!

Sa ne vedem cu bine la anul! 🙂

Si un citat care mie mi-a incalzit sufletul! Pe langa vin fiert cu scortisoara, mar si cozonac! 🙂

“Watch, listen, shoot every day, not everyday, look at the best work obsessively, give yourself time, realize you just ain’t got it when comparing your work to the very best, don’t get cynical, reinvestigate hallucinogens to expand your thinking (optional), take more photos (not optional), browse your archive and cringe, and (hopefully) smile that at least you’re not that bad anymore, thank god you didn’t submit any of those to HCSP, ponder what you’ll think of your current work in 12 months, see previous, rethink yourself 20 times before starting a thread on HCSP, kill your television, worship your gods then kill them, with reverence, get off your computer and go outside, take more photos, use less equipment, screw on your balls of steel, treat yourself to a cool bag that doesn’t look like a camera bag (as much), shoot some chromes on a 40-year-old rangefinder, look at some of the best 40-year-old photos taken on a rangefinder, smack your head and say holy **** they were good, take pictures, make glorious failures, take pictures, loosen the **** up, buy an ipod and listen to Tom Waits (vintage) while on the street, and realize that good street photography is ****ing Everest so lighten up, give yourself a break, celebrate good work, learn, learn, learn, shoot, shoot, shoot and most importantly, get the **** out the door.

At least that’s what I tell myself, and I have to commute.

Oh yeah, and smile. Always smile.”

– Tom Hyde

Merry X-mas!

In primul rand as vrea sa va urez tuturor un Craciun minunat alaturi de cei dragi, masa plina de cozonac, multa fericire si nu in ultimul rand cadouri! 🙂

Am reusit sa inauguram noul studio, cadoul nostru de la mos! 🙂 Ne bucuram tare mult si va asteptam cu drag 🙂

Intre timp postez primele cadre pe un film Fujifilm NPS 160, scanate cu scanerul Plustek 7200, care e un scaner dedicat pentru format 135. Din pacate, in unele cadre se vor vedea amprente. Vechea problema care se intampla la chioscurile unde se developeaza in proces automat C41. Anyway, sper sa va placa 🙂

Vi-l prezint pe Benny! 🙂 O sa il regasiti si in pozele ce vor urma…mai sunt multe de scanat.